|

[Index] Case Number 606 Makes History

A wagon drawn by two horses rattled around the bend in the road and rolled into sight. Holding his breath until the rig was even with his hiding place, he stood, then stepped off onto the back of the wagon. Driver Fred M. Searcy was lost in thought. He had driven the first class mail stage between Three Creek and Jarbidge for a couple of weeks and wasn't sure he wanted to keep the job. Too damned cold and the worst of winter was yet to come. A hard bump startled him back to reality. Thinking he had run over a rock, he gave it no more thought. He glanced up and saw he was on the outskirts of the gold camp.That was his last look at the world as an explosion behind his left ear propelled a .44 caliber slug through his head blasting him into eternity. Down the road a few hundred feet, Rose Dexter sat at her kitchen table. She heard the gunshot but dismissed it as just some of the boys celebrating a bit early in the evening. She glanced at her clock. It was almost 6:30 p.m. A couple of minutes later she heard the Jarbidge stage approaching and stepped out onto the porch. The man driving was wrapped in a tarp and didn't look up as the rig passed within twenty feet so she didn't call out to him. Postmaster Scott Fleming pulled out his watch and checked the time. It was nine p.m. The mail stage from Three Creek was officially late. He sent a man out to ride a mile or so north to check. Fleming stepped back into the post office and phoned Rattlesnake Station and was told the stage had left there several hours previously. He rang up Rose Dexter and she told him the rig had passed by her house about three hours before. Fleming was sure something had happened. Bad news travels fast in a small town and several men had come to the post office for word about the stage. Four of them volunteered to search for the rig. For an hour they found nothing. Just about ready to give up the searchers decided to check out an old lane that branched off the main road. They rounded a clump of willows and their lights illuminated the lost stage. The horses stood, still in harness, frosted with snow. On the front seat of the open wagon was a canvas-covered shape. It was Searcy, head hung to one side and obviously dead. His body was transported to the post office and guards were stationed around the wagon area. At first light in the morning, Fred "Curly" Morse was searching around the bridge over the Jarbidge River and found a wadded up black overcoat. The garment had a couple of rips on the sleeves. Morse's wife watched the coat while he trotted into town to get more searchers. A blue bandana, a sack containing $182 in coins, and a white shirt weighted with rocks were found in the river. In the area around the stage wagon other items were picked up. In all, close to fifty pieces of evidence, ranging from a slashed mail bag to a letter stained with a bloody hand print were collected and displayed at the post office. Around three thousand dollars in cash were missing and no one knew how much, if any, money might have been enclosed in the torn open first class letters strewn about. The sack containing $182 was the only money ever recovered. What happened to the rest is not known. Phone calls were made to postal inspectors and to Elko County Sheriff Joe Harris. Roads from the Nevada side were closed by snow drifts and they had to come in from Idaho. Meanwhile, the black overcoat was being discussed by Justice of the Peace J.A. Yewell and Frank Middleton. Both agreed they had seen it around town on Ben Kuhl, a drifter who had been in camp for a few months. He usually wore a mackinaw but did, occasionally, wear a long black coat.

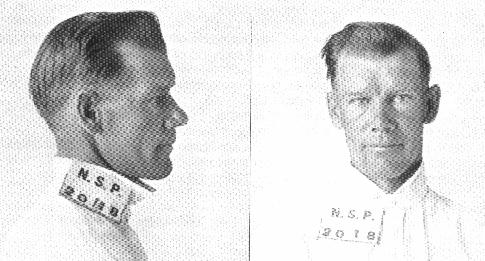

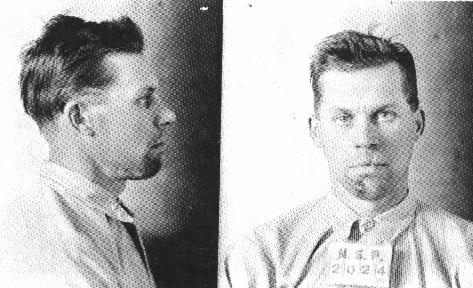

Yewell signed a complaint against Kuhl and sent Constable I.C. Hill to arrest him. Kuhl had been a cook and baker at OK mine for a month or so but recently was working at odd jobs around town. He was already known as a trouble maker. In 1903 he served four months in Marysville, California for petty larceny and was later sent to the Oregon State Prison at Salem for a one to ten year sentence for horse theft. In Jarbidge he had been arrested on trespassing charges and was awaiting trial. Kuhl was locked up. Knowing he ran with a small band of toughs, officials arrested three of his closest pals, Ed Beck, William McGraw and B.E. Jennings. Jennings, for lack of evidence, was released after the preliminary hearing. The others were taken to Elko by Sheriff Harris and District Attorney E.P. "Ted" Carville.

McGraw agreed to squeal on Beck and Kuhl. He was held in jail for ten months to make sure he was around to testify at the trials. Beck, from Finland, was known as "Cut-lip Swede." He had been in town only one week. Working half-shifts at the mines left him plenty of time to pursue his hobby of drinking. Kuhl's trial began September 18, 1907. Judge E.J.L. Taber asked the press not to report the trial because it might prejudice future jurors for the Beck case. Scores of witnesses testified against Ben. They remembered the black overcoat, even mentioning the tears on the sleeves. Constable Hill found an ivory gripped .44 caliber pistol in a traveling case under Kuhl's bed in his tent. There was a strip of bloody canvas tied to the pistol's butt ring. The gun rested on a water diluted bloodstain on an otherwise clean shirt. Bartender P.F. Woodgate testified that the firearm belonged to McGraw. On the stand McGraw claimed he gave the pistol to "Cut-lip" and that Beck told him later that Ben had done the murder. Then came two California fingerprint experts, C.H. Stone, head of the Bakersfield Police Department identification unit, and O.W. Bottoroff from Fresno. Between them they had examined 1,500 crime scene palm prints the previous year. They both stated that the print on the envelope most certainly belonged to Ben Kuhl.

Attorney E.E. Caine tried to prove Kuhl was in town at the time of the murder and could not have done it. District Attorney Carville pointed out that there was an hour not accounted for. Caine also protested the legitimacy of the palm print being admitted and claimed that all the evidence against his client was circumstantial. Jury deliberations started on the eighteenth day. In a short two hours they returned a verdict of guilty of first degree murder. A local reporter wrote that Ben was the coolest man in town when he heard the decision. Judge E.J.L. Taber sentenced Kuhl to death and offered him a choice of being hanged or shot by a firing squad. Ben said he wished to be shot. Ed Beck's trial began on October 8, 1917. The defendant was plainly frightened. A bevy of witnesses, most of whom had testified against Kuhl, gave damning testimony during the six days it took to decide Beck's fate. McGraw told the court that Beck had confided in him that the stage was going to be held up. When he asked Beck to return the gun, "Cut-lip" said his partner had it and that McGraw had better keep his mouth shut or he would be killed. Beck took the stand. Impassively and speaking in broken English, the jurors had trouble following his story. He said he had given the gun to Kuhl. The jury took two ballots; the first was nine to three for conviction, the second unanimous. Judge Taber gave him to a life sentence. "Cut-lip" would serve six years and 23 days in the Nevada State Prison in Carson City. He was paroled on November 24, 1923. Kuhl's prison experience is a different story. Just a week before his scheduled execution on January 10, 1918 he received a stay and suspension until the Nevada Supreme Court could make a final determination of his appeal. The prime argument was, of course, the admissibility of the palm print as evidence. Kuhl's attorney, Harold P. Hale, argued that such prints had never been brought before a court in the United States, England, or, for that matter, anywhere in the world. The justices ruled that the prints were admissible so Judge Taber set a new date for Kuhl to meet death - December 20, 1918. A week before his execution date the Board of Pardons met in a special session and voted three to two to commute his sentence to life. Kuhl settled down to a regulated prison life. His job was raising chickens. Every year after he became eligible for parole he petitioned for his release and was turned down. Ben continued his chicken house duties and found himself, one day, to be the longest termer in the place. Milo Taber of Elko tells of seeing Kuhl at the prison in 1943. "He was white haired and still taking care of chickens." Finally, on April 16, 1943 Ben Kuhl stood outside the prison's sandstone walls. He had been paroled by the governor. Ben was 61 years old and had served almost 28 years. He died of tuberculosis in San Francisco the following year. Well, that's the Ben Kuhl story. He didn't know he would make history when he murdered stage driver Searcy: (1) His crime was the last horse drawn stage robbery in the nation; (2) It was the first time palm prints were entered into evidence in a court trial; and (3) He was paroled by Governor Carville the same man who had prosecuted him as Elko County District Attorney.

4 October 1998

Almost every time this crime is mentioned in any Nevada history, authors write that this was the last stagecoach robbery - it was not. The vehicle was a mail stage, a buckboard-like wagon. Information for this story came from the article, "Last Horsedrawn Stage Robbery," I wrote for the Northeastern Nevada Historical Society Quarter, Winter 1981 (81-1). Research for that article came from the trial transcripts, Elko Free Press, Elko Independent, and interviews with Dr. Morris F. Gallagher, Dr. George Manilla, Florence Harris, and Milo Taber, all of Elko. Additional information came from another story I wrote, "Letters From Jarbidge" also published in the Quarterly (78-2). Anyone who want's to know more details about the robbery and murder can read the two quarterlies at the Northeastern Nevada Museum, 1515 Idaho Street, in Elko. ©Copyright 1999 by Howard Hickson. If any portion or all of this article is used or quoted proper credit must be given to the author.. |