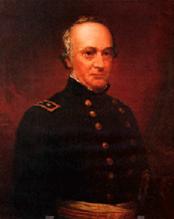

General Henry Wager Halleck, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Army. |

Life at the Fort Fort Halleck, Nevada (1867- 1869)

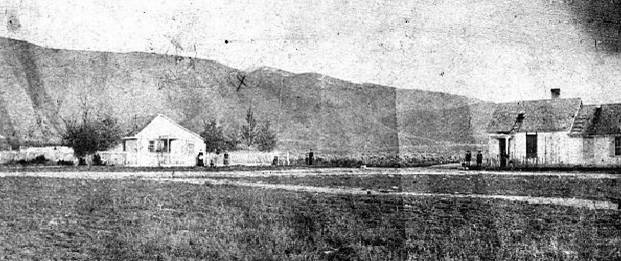

First called Camp Halleck, it was an isolated place where few military men wanted to be stationed. There were no log walls, The nine-square-mile post was at the base of the western slope of the Ruby Mountains on the banks of Cottonwood Creek where, most of the time, there was good flowing water, a necessity for any settlement.

A tour of duty in Nevada at Camp Halleck was really in the American West outback. It was not a pleasant place. The life there was downright primitive. When they first arrived at the site in 1867, soldiers had to build dugouts in which to live until permanent quarters were built several months later.

|

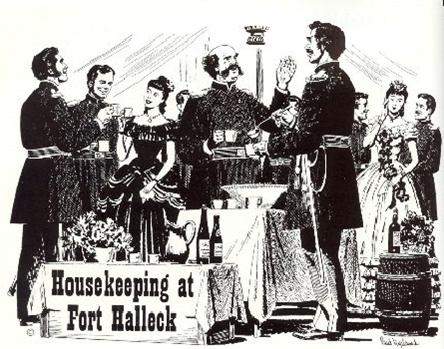

Camp Halleck was soon a two-company post. Another unit soon moved in. It included a married officer and his wife. She arrived after a long sea voyage and a bone jarring stagecoach ride. All their belongings were hauled to the fort in freight wagons from San Francisco. Much of it was lost, stolen or broken. The new couple invited the post officers and the other two wives to a party to get to know them. Everyone had on their best uniforms and party dresses. Her husband brought in the punch in a wash bowl. She almost passed out but quickly told their guests that their punch bowl was broken in the move and that the wash bowl was brand new and had never been used. The Boyds lived in a two-tent affair. The tents were eight feet square without windows. The weather wreaked havoc with their quarters. The first winter, temperatures plunged to below -30 degrees. They had a large stove in one tent and built a fireplace in the other. It didn’t help much. Their kitchen walls were willow sticks stuck into the ground and covered with sacking. The sacks leaked and were quickly replaced with old canvas. Then hides from butchered cattle were added. Still, rain and melting snow continued making it almost impossible to find a dry place to cook and those cowhides smelled to high heaven. Rations were issued to officers and their families, including flour, bacon, beans, coffee, tea, rice, sugar, condiments and soap. A luxury was dried apples, Two miles away was a trading post and local ranchers sometimes sold fresh vegetables. But, there was a catch. The locals wouldn’t accept greenbacks. That was how the military was paid. The paper money had to be converted into gold - at a 50% rate. The officers and their ladies ended up with half of their pay and then paid inflated prices for butter ($2.50 a pound), canned goods ($1.00 per can) and eggs ($2.00 a dozen). Sky high prices for those days. Their pay didn’t go very far.

In the spring, soldiers planted and raised vegetables for their mess. Through a quirk in military regulations, officers could not use or purchase any of the men’s fort grown produce.

Parties were held on nearby ranches, Halleck, 12 miles north of the post, and at Lamoille, ten miles southwest. Whether locals traveled to the fort or the officers and their ladies visited, they carefully packed their party clothes for the trip and wore everyday wear. They changed to the good stuff upon arrival.

One time, in Lamoille, the people celebrated the Fourth of July. Colonel May H. Stacy, commanding officer of the fort, read the Declaration of Independence. Post Surgeon Dr. W.L. Newland presented an oration. Troops marched in the afternoon and then fired salutes with cannons and rifles. It was a fine celebration. It wasn’t often that the enlisted men were included. The camp’s 24-member band was in demand for all the parties, outdoor festivities, and dances held in the area.

Life at the fort improved measurably when the Central Pacific Railroad tracks reached the town of Halleck in early1869. Although the base was now afforded more supplies and a few luxuries, it was still one of the most primitive military bases in the nation.

See "Men in Blue" and "Indian Ambush " for more about Fort Halleck Sources: Nevada’s Northeast Frontier, Edna B. Patterson, Louise A. Ulph (now Beebe), and Victor Goodwin, 1968, reprint by the Northeastern Nevada Historical Society, Elko, University of Nevada Press, Reno, 1991. Pioneer Nevada, Volume Two, 1956, published by Harold’s Club, Reno. Illustration from Pioneer Nevada, Volume Two. Photographs from the Northeastern Nevada Museum archives, Elko.

©Copyright 2009 by Howard Hickson

|

|