HOWARD

HICKSON'S HISTORIES

[Index]

Missouri Flat

Elko, Nevada 1869

Freighting to mining camps was the first

big business in Elko. Missouri Flat was the freighting center for a large

chunk of Nevada and southern Idaho. The place was in the vicinity of Silver

between Seventh and Ninth streets. It was loud, busy and dusty. The noise

of horses, mules and oxen was eclipsed only by teamsters cracking whips

and cursing their animals. The heavy wagons, either inbound or outbound,

caused gridlock almost daily. It was not a place for the fairer sex nor

for timid men. Most of the teamsters lived in tents down by the Humboldt

River where they could water and feed their animals.

In late August, 1869 the Weekly Elko Independent

editor observed there were 177 freight wagons down at the Flat, 100 loaded

and ready to leave the next morning. They weren't small vehicles - some

of them could haul up to 40,000 pounds for two cents a pound. The big rigs

carried mine machinery, lumber, foodstuffs, fuel and furniture.

There was also an express service for those

who could afford three cents a pound for perishable foods and other supplies

needed in a hurry. Fast freight was loaded into smaller wagons, usually

pulled by mules or horses. Oxen plodded ten to twelve miles a day while

mules and horses could do twice that.

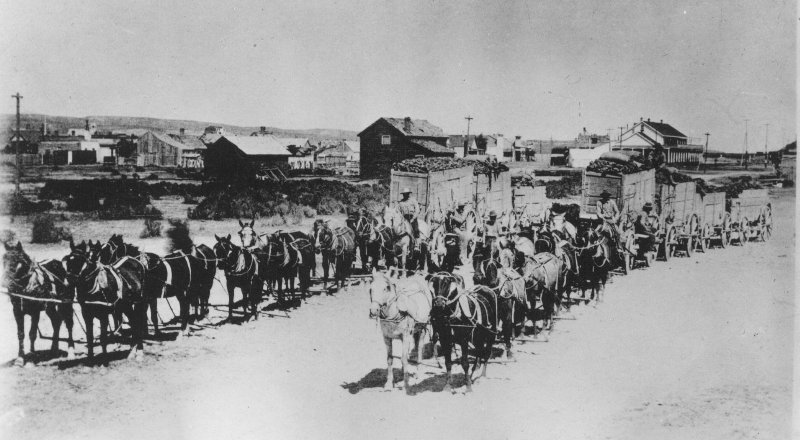

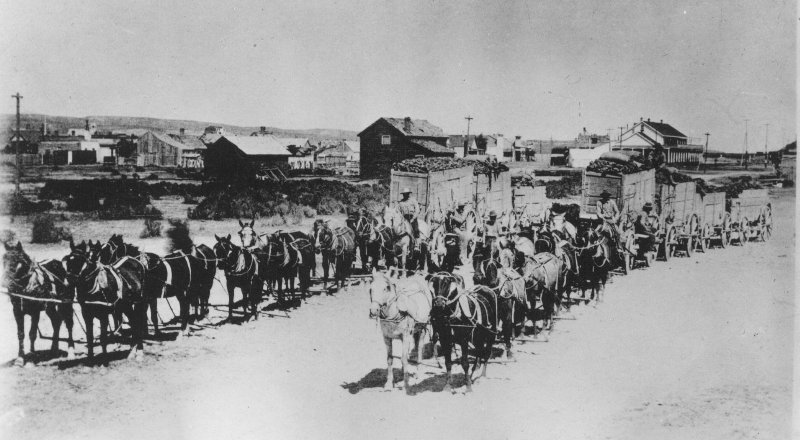

Two rigs loaded for Tuscarora in the 1880's when horses

and mules had

replaced slower oxen. Photo from Northeastern Nevada

Museum, Elko.

Twenty to thirty rail cars of machinery and

supplies arrived daily in Elko. That's upwards to 300 tons for unloading

and shipment to mining camps. Operating all year, good weather or lousy

conditions, freighters pulled loads 200 miles north to Silver City, Idaho

Territory; 120 south to Hamilton, Nevada; to Eureka and White Pine; and

to all places in between.

Usually there were three or four wagons with

upwards to 16 oxen doing the grunt work. Bulls, weighing around 1,600 pounds,

were the beast of burden of choice. Even so, they had trouble in hilly

or mountainous terrain. One bullwhacker, taking a big load to Eureka, said

he frequently had to unhook the wagons and have the oxen pull one or two

wagons until the four were sitting on top of a hill. Once there, he hitched

up all his wagons and animals to continue his haul to the mining camp.

In 1880 oxen sold for $150 to $200 a yoke

(two animals). Considering that a bullwhacker needed as many as eight yokes

meant a big financial stake. With that much cash invested it was essential

that the teamsters take care of the animals. Every wagon carried large

barrels of water when good water was scarce on a route. Many times water

was nonexistent or was so full of alkali it was not good for either man

or beast. During summer the rigs were stopped every hour and each ox was

given a pail of water.

Although horses and mules were used from the

beginning, it was in the middle1880's that speed became important and oxen

teams were gradually replaced by horses and mules. On the pull to Tuscarora,

oxen teams and wagons usually took about one week to make the trip. The

record to the silver camp was a round trip in three and one-half days using

horses. The wagons, loaded with 12,000 pounds of freight, usually took

two days to get there and one and one-half days to return empty.

Freight businesses were subject to the booms

and busts of mining. As ore diminished there was, of course, less business.

A couple of companies, when ore was no longer available for the return

trip, began taking on passengers bound for Elko. There are no records of

success in this venture but the idea was probably a bust. Who would want

to ride in a freight wagon but the fare of only $10 might have been attractive?

With mining camps failing and their populations

leaving, the need for those behemoths of the road stopped. Missouri Flat

gradually became quite as the men, animals, and wagons left. No longer

was there daily gridlock. The crack of long whips and the bellowing of

the teamsters cursing the animals were gone. Paved streets, homes, and

businesses took the place of the Flat.

An boisterous but essential part of 19th century

American West died with the mining camps. As with most places then, Missouri

Flat is just a memory.

Howard Hickson

March 9, 2003

Sources: Elko, One of the Last Frontiers of the West

by Howard Hickson, 2002; A Sagebrush Saga by Lester W. Mills, 1956.

©Copyright 2003 by Howard Hickson.

[Back to Hickson's Histories Index]

|